BEFORE it met a violent end last month, China’s stockmarket rally was more than just your run-of-the-mill mania. It was political. Many investors called it a “state bull market”, believing the government was firmly in control, guaranteeing that shares would only go up. Others said it was an “Uncle Xi bull market”, as if it were a gift from China’s top leader, Xi Jinping. State media lent their official imprimatur to the frenzy: a People’s Daily editorial in May, shortly before the bubble popped, predicted the good times were just beginning. Buying stocks “is buying the Chinese dream”, proclaimed a top brokerage.

The plunge of nearly a third over the past four weeks has left the dream in tatters. Although the market is still up by 75% over the past year, many mom-and-pop investors were late to the party. Less than a fifth of respondents to a large online survey by Sina, a web portal, reported making any money from stocks this year.

For the government, the fall is damaging. Officials are seen to have promised the population a bull market, only to lure them into a bear trap. A flourishing of gallows humour in mobile-phone chat groups captures the sentiment. “Friends, don’t run, we’re here to save you,” cry the valiant soldiers in one joke, representing the state coming to the aid of the beleaguered market. Their refrain soon turns to, “Friends, don’t run, or we’ll shoot you.”

The warning signs had been flashing for some time. ChiNext, a venue for high-growth companies, reached a price-to-earnings multiple of 147 at its height in early June, in the same region as American tech stocks during the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s. When share prices started falling, many assumed that regulators would stay on the sidelines and let the correction unfold. But policymakers lost their nerve after the market fell by nearly 20% and negative headlines started to pile up, even in the domestic press.

Attempts to steady the market have been frantic and largely futile. Interest rates have been cut; short-selling capped; IPOs halted; share-buying schemes, backed by central-bank cash, hatched. “We have the conditions, the ability and the confidence to preserve stockmarket stability,” blared thePeople’s Daily, as the rout continued.

The CSI 300, an index of China’s biggest listed companies, fell by 16% in the eight trading days after the rate cut. Some $3.5 trillion was erased from China’s stockmarkets, more than the entire value of all listed firms in India. By the end of July 7th trading in over 90% of Chinese stocks had been suspended, either at the request of the firms concerned or because they had tumbled by the daily limit of 10%. “The government won’t let us take our money out of the market, and we don’t have the confidence to put any more into it,” says Wei Xinguo, a chef at a noodle restaurant in Shanghai and one of the country’s 90m stockmarket investors.

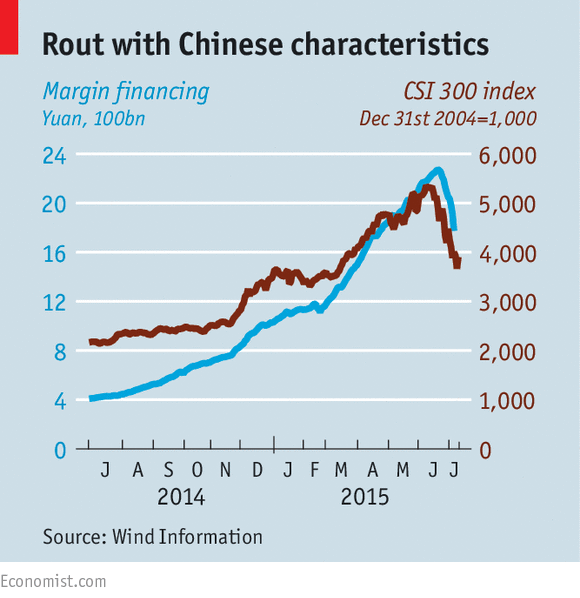

The preponderance of punters like Mr Wei makes Chinese stockmarkets volatile. Retail investors account for as much as 90% of daily turnover—the inverse of developed markets, where institutions dominate. But the government’s inability to calm things down despite such heavy-handed intervention is unprecedented. It stems from the degree to which the rally was predicated on debt (see chart).

At its peak, margin financing reached 2.2 trillion yuan ($355 billion), or about 12% of the value of all freely traded shares on the market and 3.5% of China’s GDP. Both proportions are “easily the highest in the history of global equity markets”, according to Goldman Sachs. With Chinese shadow banks and peer-to-peer lenders also offering cash to investors, the actual amount of leverage in the market is likely to have been even higher. That helped propel the original rally. It is now compounding the downturn as investors scramble to sell their holdings to cover their debts.

The sharpness of the slide has raised worries that Chinese growth itself is about to fall off a cliff. Mercifully, the stockmarket appears to be as disconnected from economic fundamentals on the way down as it was on the way up. At the same time as shares nearly tripled from the middle of 2014 until early June, China slouched to its slowest year of growth in more than two decades. In the past couple of months the economy has actually started to improve. A burst of government spending on infrastructure looks to have stabilised the industrial sector; property prices, long in the doldrums, have started to tick up again.

The stockmarket is still just a small part of the Chinese economy. The value of freely floating shares is about a third of GDP, compared with more than 100% in most rich countries. Stocks account for just 15% of household assets, so their slump should have limited impact on consumption. The systemic consequences of the margin debt are also limited. The funding has come from brokers, not banks, and equates to less than 1.5% of total bank assets.

There will undoubtedly be some spillover from the panic. Futures contracts for raw materials from lead to eggs fell by their daily limit on July 8th as investors sold to realise some cash. On international markets, the price of iron ore, which China consumes the bulk of, slid. Yet risks of a systemic nature remain remote.

The long-term consequences could be severe, however. Like any big, sophisticated economy, China needs a healthy equity market. For investors from households to pension funds, stocks should, in theory, provide a better return over time than low-yielding bank deposits. For companies, equity financing is an important alternative to bank loans, helping to reduce their reliance on debt. The scrutiny and rules that come with a share listing should also help improve corporate governance.

Before the crash, China was inching towards reforms that would fix some of the distortions in its market. A programme launched last year connected markets in Hong Kong and the mainland markets. Though subject to strict quotas, it promised to introduce more of an institutional presence on China’s exchanges. Regulators had stepped up supervision of insider trading and had also planned to change the way initial public offerings work, giving firms more control over the timing and size of their listings. But as the government’s all-out, if inept, response to the crash shows, it is reluctant to cede control.

Meanwhile, the crash has scarred a generation of investors. Xu Pengfei, a 25-year-old fitness coach, put 100,000 yuan in the market in April, two months before the crash. He managed to get out before losing any money but has no plans to reinvest. “I don’t have much faith now.”

http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21657345-china-learns-stocks-are-beyond-communist-partys-control-uncle-xis-bear?fsrc=scn/tw/te/pe/ed/unclexisbearmarket